Judge Finds Odors From Store Are Not Pollution

BY JAMES BARRON | AUGUST 2, 2010

Nineteen pages into a ruling on an insurance case, a federal judge did not actually declare that the defendant’s claim — that odors from a restaurant should be considered pollution — stank. The way Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald put it was, that argument was “malodorous to this court."

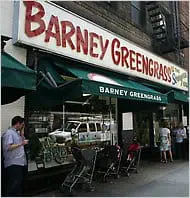

The defendant was an insurance company that held a policy for Barney Greengrass, the century-old Upper West Side restaurant that has served everyone from Isaac Bashevis Singer to Brad Pitt.

Barney Greengrass sued the insurance carrier, Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Company, after the restaurant itself was sued by a man who lived in an apartment upstairs, Theodore R. Bohn. Judge Buchwald summarized his case like this: “Overpowering food odors — emanating from a commercial kitchen exhaust vent underneath one of Bohn’s windows — permeated his living space and rendered it unusable."

Barney Greengrass, Judge Buchwald noted, was “never actually identified in Bohn’s complaint," which she said was directed against the building, at 176 West 87th Street, and its managing agent. The building, a co-op, in turn sued the commercial landlord that controls the Barney Greengrass storefront at 541 Amsterdam Avenue.

When that happened, Barney Greengrass filed a “general liability notice of occurrence/claim" with Lumbermens. Lumbermens said that food odors were pollution, and that pollution was not covered by the policy.

The judge said the policy did include a “pollution exclusion," which typically means that damage from pollutants is not covered. But she all but snorted at the idea that Lumbermens had invoked it.

“Insofar as odors are at issue in this case," she wrote in her 25-page decision, first reported on the Web site Law.com, “we find as a matter of law that they do not fall within the pollution exclusion." She said that the odors “were not the sort of industrial environmental irritants or contaminants to which pollution exclusions typically apply."

She also noted that “odors" were not among the terms mentioned when the policy defined “pollutants." “If Lumbermens wanted ‘odors’ in general or ‘operational odors’ in particular to be included in its policy definition of ‘pollution,’ " Judge Buchwald wrote, “it could have drafted its exclusion accordingly."’

A lawyer for Barney Greengrass, David Jaroslawicz, said Judge Buchwald’s decision included more than a whiff of justice.

“You know what happens with the insurance carriers," he said. “Whenever you make a claim, they find a reason to disclaim. Pollution means a gas station that lets oil seep into the ground or some chemical plant that discharges into the water. It doesn’t mean there is allegedly an odor in a restaurant. You walk into H&H bagels, it smells of bagels. You walk into Zabar’s, it smells of Zabar’s. You go into a store — there’s a new hamburger store at 84th and Broadway, Five Napkin Burger. They’re busy. It smells of burgers. Obviously, I think the judge was right."

A call to David M. Pollack, a lawyer for the insurance company, was not immediately returned.

Article posted from the New York Times